Welcome to the 5 Questions Series. Each week, I’ll ask five questions of some of my favorite authors, editors, publishers, and other industry professionals. This week, I’m talking with Kendra Preston Leonard whose work in opera and academia challenges the status quo and uplifts voices too often left out.

Your academic and creative work both focus on bringing marginalized communities to the forefront. What are some of the biggest challenges you see in representation today, and how do you navigate them in your own work?

The hegemony of white men is still an issue in both academia and the arts. For example, in 2024, Houston Grand Opera premiered Intelligence, a new opera it had commissioned. The plot focused on the work of two women—one white, one Black—who ran a spy ring for the Union during the American Civil War. The opera included references to the Black woman’s African ancestors, and music that was meant to represent their soundscape. While HGO did bring in Jawole Willa Jo Zollarn, as the production’s choreographer, the composer and librettist were both white men—Jake Heggie and Gene Scheer. What made this story theirs to tell? I’m not saying that men can’t tell women’s stories, or that white people can’t write works about Black people, but in a story centered on women and with a significant scene depicting Africa, I’d at least have liked a woman or Black artist to have a major role in the creation of the words and music. This was a missed opportunity to showcase women or nonbinary creators who might have told a story that offered greater representation both on and off stage.

In my creative work, I write about what I know and believe in, and teach the same things. One of my operas with composer Jessica Rudman is an adaptation of my novella in verse Protectress. The opera is written for ten women or nonbinary singers. At a talkback after a workshop performance of the first act, someone asked if we were going to add characters who were men to it. We both said, “No.” And the person seemed very flummoxed. But I was thinking of Ruth Bader Ginsberg’s “When there are nine.” We don’t need men in that opera, just as the Supreme Court doesn’t need to have men on it. I’m very firm about what projects I take on being aligned with my own values. I’ve just finished the first draft of a libretto for an opera called This is Jane with composer Angela Elizabeth Slater about the famous Jane collective, a Chicago-based group of mostly women who provided illegal but safe abortions for as many as 11,000 people in the years leading up to the legalization of abortion in 1973 in Roe v Wade. The Janes are heroes, and that’s how I’m depicting them. I’m also showing them as the very diverse group they were—white, Black, Latine, disabled, old, young, of every size. And every libretto I write has a casting note attached: some state that certain characters must be sung by certain kinds of performers; others are broader and say that the roles can be sung by any kind of body: disabled bodies, trans bodies, fat bodies, any body. And the performing arts organizations groups I work with generally embrace that and support it. But we still have a long way to go, so I also encourage my colleagues and students who write for the stage to do the same. My current workshop participants—members of the Guerilla Opera Writers’ Collective—have really leaned into this, and I love it.

Academia—at least some fields—is much more welcoming of projects that center minoritized communities. Nonetheless, there remain biases against the disabled, the fat, and the neurodivergent. As a fat, disabled, autistic woman, I get pretty tired of reading books about people like me written by people who have no idea what it’s like to be any of these things, or who haven’t spoken with those of us who are. Fat activism and Fat Studies have been around since the 1960s, but fatness remains a socially acceptable thing to condemn or mock. Academia often points to the lack of available primary sources surrounding the lives and work of minoritized communities, but fortunately scholars are always developing new methodologies that can help counter this. For the last several years, I’ve been researching the role of women and BIPOC musicians in silent film music. This is an area in which not only are the primary sources written almost exclusively and biased in favor of white men, much of the secondary scholarly and popular literature to date is also biased in the same way. While I’ve been able to comb through primary sources and find a good deal of information about white women, finding BIPOC musicians of any gender has been difficult. Fortunately, there’s an approach used in film studies and other disciplines I can use: speculative historiography, in which scholars posit “what-if” scenarios based on what knowledge is available. This is widely used in history, media studies, gender studies, and other fields, but musicology—music historiography and theory—is always about 20 years behind everyone else in the humanities and so is less enthusiastic about the idea. But I persist. When I was teaching musicology more frequently, I also made sure that what I was teaching was as inclusive as possible, and I taught people to look really critically at the materials they were being taught to rely on for understanding music historiography and theory. On the first day of a class with a textbook I would never have chosen but which was foisted upon me by my chair, I asked students to look in it and tell me how many pages they had to go to find a non-white, non-man composer or other musician even mentioned. One woman shot her hand up: “eighty pages!” I told them to take their books back to the bookstore for full refunds. I didn’t get asked to teach there again, but every time I see one of those students, they remember that.

In both academia and the creative arts, I really want people to create and read or see or hear work that pushes them into activism, and I want publishers and institutions and performing groups to help facilitate it through talkbacks or initiatives that help the community. In 2018, when the new Queer Eye was aired, Tan France said, “The original show was fighting for tolerance. Our fight is for acceptance.” Well, my fight is to get people from saying “that’s fascinating and important” to “I’m gonna go donate/march/advocate for this issue.” I want people to set down my books or leave a performance venue and go actively do something that makes a difference. Program more music by nonbinary composers, give money or time to a mutual aid abortion fund group, teach your students equal numbers of pieces by white and BIPOC composers, volunteer at a crisis hotline. Write poetry, give readings, give books by nonbinary and women writers to your friends.

As an educator, what strategies do you use to encourage and support storytelling from those who may not see themselves reflected in traditional media?

Write what you want to see and hear and identify your allies in the world in which you want to work. You want better representation of queer folks on stage? Then your opera or play or musical or song cycle or whatever should focus on that—and truly embrace it. Don’t avoid a sex scene, a long kiss, an intimate moment just because some audience members might be uncomfortable. You’re not writing for them. You want better representation of mental illness on stage? Write from your own experiences but also interview other mentally ill people and let them read it and use their feedback. Be forthright and non-apologetic. Require that the main roles be sung by people who are mentally ill, and that any production have resources on hand to help performers if needed (trauma in opera and the ethics of care is something I’m just starting to write about but I’ll save it for now). I’m autistic and have an upcoming project with an autistic character. There are several plays and operas and other works out there that are “about” autism, in that a character or two “act” autistic (which is usually a set of behaviors defined by neurotypical people). Without the input of people who are Actually Autistic, these easily become caricatures. I want to change that by creating work that reflects my own and other people’s experiences as neurodivergent in a neurotypical world.

As for finding allies, I tell people to go to/watch lots of performances. Look at what the local arts organizations in your area have put on and go to performances by the ones that want to tell stories like yours. Tell performers and directors you like what they do, that it resonates with you. Join online groups and Discords and go to meetups, if you can. Finding your people can take time and can be hard, but there are people who really do want to hear the same stories that you want to tell. And often smaller organizations and groups are more in it for creating better spaces and places for minoritized communities than the big, rich organizations. The Metropolitan Opera only just got around to putting on an opera by a Black man, but the Opera Theatre of St. Louis has been premiering new works by composers and librettists of color for years. Director, singer, producer, and drag king extraordinaire Danielle Wright produces gender-swapped operas with trans singers. Omar Najmi and his husband Brendon Shapiro founded Catalyst New Music to produce Omar’s opera This is Not That Dawn, about the Partition of India, and to support the creation of new art song. You can find your people and tell your stories. Be patient and be engaged.

I’m absolutely fascinated with your background in opera and writing librettos. Do you see contemporary opera challenging the trope of the tragic or mad woman?

I wish there were more challenges to it. There are still far too many operas that are about women’s trauma and end with dead women on stage. I was at Opera America’s Women’s Opera Network online conference in March, and we talked about the continuing push by primarily white audiences for minoritized groups’ trauma to be central to any stories about that groups. There are, unfortunately, women librettists and composers writing about women’s trauma in exploitative ways, feeding audiences stories of how being a woman, and particularly a sexual woman, equates with death. We need more roles for women in opera in genera: my colleague Hillary LaBonte, found that of the operas written and premiered between 1995 and 2019, only 43% of the roles are for women, despite women vastly outnumbering men among graduates of schools with degrees in voice and opera. And few of these operas received second productions—this is common in the opera world—so these roles mostly go unknown and unsung.

Composer Kamala Sankaram has said that she works to refute the idea that strong women in opera have to die, and her opera Thumbprint (2009-14), with librettist Susan Yankowitz affirms that—in this work, the protagonist, the first Pakistani woman to see justice done for her rape, uses the settlement money from her case to start a school and refuge for other women. In Kaija Saariaho (composer) and Amin Maalouf (librettist)’s opera L’Amour de from 2000, it is the man in love who dies in the arms of the woman; she then enters a convent. In their 2006 opera Adriana Mater, the focus is on sisters who survive horrific treatment during a time of war in their country; and in Saariaho’s last opera, Innocence, which has a libretto by Sofi Oksanen, the women of the story are the strongest figures in it. Jennifer Higdon (composer) and Gene Scheer (librettist)’s opera Cold Mountain (2015), the character of Ada, a woman, lives while her lover, a man, dies. There are operas about same-sex relationships, of which Paula Kimper (composer) and Wende Persons (librettist)’s 1998 Patience and Sarah, is probably the best known. It has a genuinely happy and optimistic ending and deserves far more performances than it’s had. Ana Sokolović (composer) and Hannah Shepard (screenwriter)’s opera Svadba is for six women, and it too has a happy ending.

Addendum to the above question which I know means I’m cheating on the five questions theme here. How do you personally approach opera as an activist art form?

I ask myself (and my students) these questions: Why do you want to tell this story? Why do YOU want to tell this story/is this YOUR story to tell? Why do you want to tell THIS story? What’s your goal in telling the story? Who is your audience? And How does this work contribute to equity, inclusivity, and diversity in opera? So every time I get an idea for an opera libretto, I put myself through these questions. That’s step one, checking to determine if it really is activist.

Step two is focusing on stories that can actually educate or change people’s minds or do social justice work. My opera Protectress is about pushing back against victim-blaming in sexual violence and recognizing that in a patriarchy, women aren’t always raised to be each other’s allies. I want people to leave that thinking about how to be anti-rape, how to be supportive of victims. I have a work in progress on the 504 Sit-Ins, an important event in disability history in the US. Disability activists, Black Panthers (some abled, some disabled), clergy of different faiths, all sorts of people came together in San Francisco and held a sit-in in government offices until the government did its job regarding accessibility and accommodations. It’s designed to get people thinking about how disability rights benefit everyone and taking action to support those rights.

Step three is writing for the widest possible range of performers as I can. You may have noticed in my answer above about tragic or madwomen in opera that none of the operas I mentioned have roles explicitly for or even indicating that it would be ok for them to be sung by trans and nonbinary performers, and that’s a big problem. The opera world is full of trans and nonbinary vocalists, and opera creators need to make room and make roles for them. I encourage my colleagues and students in libretto writing to write characters that can be performed by anyone who wants to perform that role and to specifically create inclusive works. I was so happy when a workshop participant recently specified that major roles in their libretto “must be cast with non-binary and/or plus-size performer[s].” This also holds for disabled, fat, and neurodivergent performers. I include language for this at the top of every libretto: “the librettist encourages the intentional casting of diverse performers including those who are plus-size, disabled, nonbinary, trans, or have any other kind of marginalized bodies. Stage directions involving movement and touch should be freely adapted by and for disabled performers as they prefer.” If I have the luxury of getting a say in casting and working with the director or a production of one of my works, I make a point to go over this with them and lean into it in casting.

Step four is pairing the work with partners who will benefit from it and inform it. I try to partner with organizations that will benefit from the work. For my piece “My Skin,” with composer Angela Elizabeth Slater, we use the story of the mythical selkie to address domestic/intimate partner violence and the need for resources for it, we’re doing outreach about domestic/intimate partner violence at performances and I give royalties I make from the sale of the piece to the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence. Another piece in works about mental health will work closely with support organizations.

Step five is teaching. Very few librettists have had any sort of formal training about the art form and all of the issues that go along with writing for opera today, and I want new librettists to have deep knowledge of what they’re getting into as activist artists. I’m the Teaching Artist in Libretto Writing with Guerilla Opera, which bills itself as “a punk ensemble that embodies are that emerges from those who challenge the status quo. We engage in rebellious works of opera theater, question the established norms, and call for radical change.” This my ethos as well. Be punk, do opera. Or should it be do opera, be punk? Anyway, I also base a lot of my teaching philosophy and praxis on anti-racist and other anti-bigotry writing approaches, drawing from Felicia Rose Chavez’s The Anti-Racist Writing Workshop and Matthew Salesses’s Craft in the Real World. This is the ethical way forward in any kind of creative writing.

I’m thrilled you’re a fan of flash fiction and I love the idea that both flash fiction and librettos require precision and conveying big ideas in small spaces. What lessons can librettists learn from studying flash fiction?

Everything! Flash relies on compressing a ton of information into a small space, and/or focusing on only what’s essential to the immediate story. In the opening scene of an opera, audiences need to get an idea of who the characters are, where they are in both time and space, and what’s going on in fairly quick order. Flash writers are excellent at setting up the frame of the story very quickly. Flash is also good for helping librettists think about non-Western and non-traditional narrative structures, because there’s so much flash that plays with conventions and experiments with form in storytelling. A new exercise I used recently was to ask librettists to tell their story in 100 words or fewer. We practiced with operas from the inherited repertoire—the pre-1950 operas that most opera companies perform today—and it was fun and revealing and got us all thinking about how we communicate within limits like time and space.

What additional shifts would you like to see in how historically excluded people are represented across media, including in opera, flash fiction and beyond?

More, more, more. More representation, more stories about joy within the lives of people from historically excluded communities, not just trauma. More depictions of how people from such groups live and thrive and innovate and simply are. In the opera world, directors have (mostly) rightly done away with blackface, and I want it to be equally taboo for a disabled character to be played by anyone other than a disabled performer, for a fat character to be played by anyone other than a fat person, and so on. I also want to see disabled, fat, nonbinary, BIPOC, or trans performers in roles that have traditionally gone to straight, abled, cis, white people. Give me a fat Jo in Little Women, give me a disabled Milica in Svadba, give me trans performers in Kate Soper’s Here Be Sirens (2014). Also, no inspiration porn.

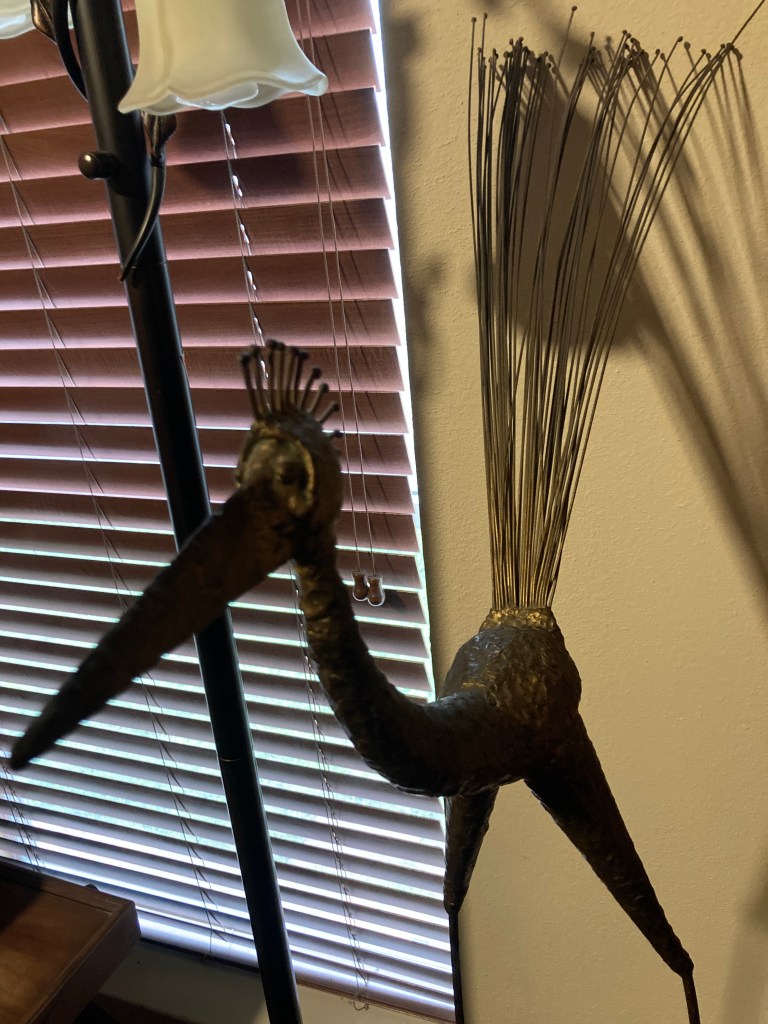

Bonus question: Have you ever taken a picture of a weird bird?

Does it have to be a real bird? This weird bird sculpture was my mom’s and she adored it. For a long time I thought it was hideous, but I grew to love it. My spouse and I drove 17 hours each way to fetch it when I inherited it, and now it hangs out with my books.

You can find me and links to Kendra Preston Leonard’s stuff (including a werewolf version of All’s Well That Ends Well, lots of poetry, and audio/video and scores for operas and songs here.

New libretto writing classes opening soon! More information available here.

Leave a reply to jasminafritter1998 Cancel reply