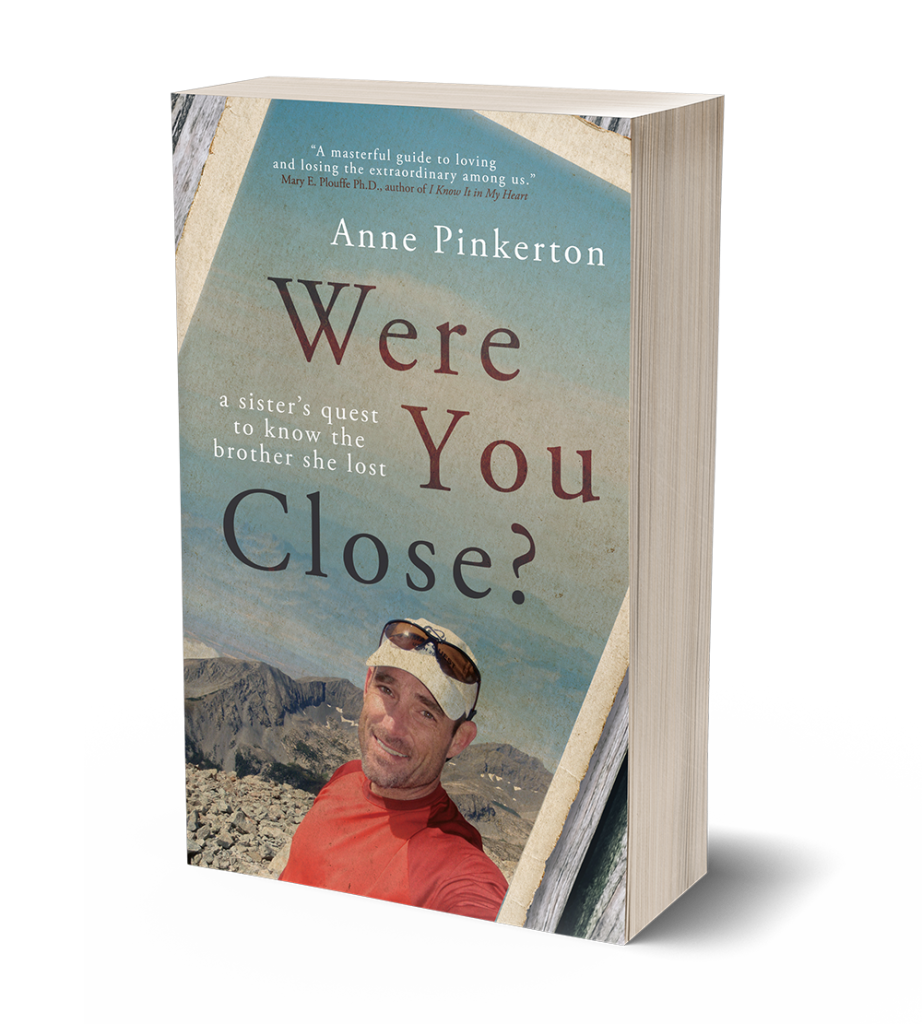

Welcome to the 5 Questions Series. Each week, I’ll ask five questions of some of my favorite authors, editors, publishers, and other industry professionals. This week, I’m talking with Anne Pinkerton.

Welcome and thank you for agreeing to talk with me. You write a lot about grief and the loss of your brother. Besides your book, you have written essays on the topic, including an excellent one I just read called, “Shitty Anniversary.” So, I’m excited to talk with you today and loss and creativity.

Thank you! That’s on my blog, TrueScrawl.com, where I publish when inspiration strikes and I want to say something timely. And I’m always struck on the anniversary of David’s death, which is the topic of the post you reference. Everyone I know who has lost someone remembers vividly the day it happened. And, frankly, even if some comforting or happy memories surface, those anniversaries tend to be overarchingly shitty, because the reality of the death insists on being remembered, too. I guess I want to be honest about that.

I’m wondering about the process of writing a book so close to your own feelings—how long did it take to write the book and what was your self-care process while writing it?

My writing about these subjects began in a bereavement writing group, a safe — and private — space to begin to process my experiences with others who were going through similar stuff. To this day, I’m exceedingly grateful for that group because they helped me sense my work had resonance while offering community, gentleness, and great compassion while I bled on the page, so to speak.

It’s hard to answer how long the book took to finish because it was produced in such a piecemeal way at the beginning, starting in that very group, long before I envisioned publishing any of it. I took the story to grad school a couple of years later, and an early draft became my thesis. I took a year off from the manuscript, and returned to it with fresh eyes at my first week-long writing residency (one of the greatest gifts I’ve ever received), where I finally finished the book. So, I tend to say the writing took three or four years if you compiled the actual drafting time, but it truly spanned a ten-year period because of all the breaks.

Which leads me to self-care when writing about the worst things that ever happened to us. Breaks are essential. To go headlong into my extreme grief over the sudden death of one of the most important people in my life without coming up for air a lot would have been impossible. I cried an ocean during the making of the book. I had to exercise, rail at the universe, give up and start again. And I don’t think I could have done it at all without a great therapist, amazing professors and classmates, a supportive partner, and the best friends anyone could hope for.

I’m so glad I pushed through.

So many of my author friends talk about the brutal reality of agent and publisher shopping, especially when a work is so closely tied to their real lives. What was your publishing journey like?

I took a fabulous course on writing book proposals, and left armed with the necessary cover letter, comparative titles, target audience, and on and on. I should note, I am also a marketing professional by trade. But it is brutal. Attempting to commodify my pain and my family’s crisis seemed almost self-exploitative. That was the hardest marketing documentation I ever had to put together.

When I started pitching agents, if I wasn’t ghosted entirely, I often heard how the writing was great, but that they couldn’t sell a grief memoir. I just wanted to yell, But there are hardly any books about sibling loss out there! Brothers and sisters really do die! All the time, it turns out. And they feel so alone. Not giving them books makes them feel even worse — trust me.

(Also, Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking, anyone? Just a little New York Times bestseller about the agony of grief. But anyway… I know I’m not Didion. Just a mere mortal.)

After about 100 queries for representation, dispirited but unwilling to throw in the proverbial towel, I pivoted in my efforts and started looking at indie publishing houses, and that changed everything. Small presses lack the resources to do some big things, but they make up for so much through their willingness to take a chance on first-time authors writing stories that are far from beach reads. When I found Vine Leaves Press and read their acquisitions editor’s note about my manuscript, I knew I had finally landed in the right place, with people who really got it.

What I say to people interested in doing this is that there is no magic to landing your book somewhere unless you are already famous for something else or have great connections in the publishing world. My mantra and only real advice is: believe in your own work, and persist.

I notice you also write poetry. How does poetry inform your non-fiction work or vice versa?

That’s my original writing identity. (Just ask my mom, who still has my poem about winter drafted at age eight framed on her dining room wall.) Something about poetry can’t be severed from anything else I write — it’s a sensibility I suppose, or an approach to language that feels almost innate at this point. Poets adore description, metaphor, and rhythm in our lines, and that goes for my creative nonfiction work, as well. Nothing makes me happier than when people describe my prose as lyrical because it feels like I’ve hit the best balance of both worlds.

And I have always written about myself and my life regardless of the form it takes. Just the craft element is different. I’ve switched short pieces back and forth between poetry to prose to find the right container to hold the story I’m trying to tell.

What advice would you give to a writer who wants to tell a story about their own life, but is worried about whether the story is really theirs to tell, or what the rest of the family might think?

This is such a tricky question, and there isn’t one answer. It’s personal to each writer, and I’ve seen a variety of approaches play out depending on the writer and situation: some authors fictionalize their personal stories, names and identifying details get changed, releases get signed. There are ethical and, occasionally, legal considerations.

My approach is fairly straightforward and taken from Anne Lamott: “You own everything that happened to you. Tell your stories.” I sincerely believe this, and clutch it to my bosom.

There’s also the second part of her quote, which gets at the fact that what happens to us often includes others: “If people wanted you to write warmly about them, they should have behaved better.” While true, that one can get us into trouble if we take it to mean we can be reckless when rendering a real person on the page, if we abuse someone’s privacy, tell lies about them, or use our writing as a tool for revenge.

I do everything I can to ensure the people in my stories are considered with great care, treated as full human beings, that they are not villainized, and are only there to serve the purpose of the story. It can be a slippery slope. People do sue sometimes when they are angry about their portrayal. While they don’t often win, it can be hellish for the writer.

What are you working on right now?

I’m almost always playing with a poem or essay — or twelve (at least in my head), and a second book has been chewing on me for years, which I hope will end up being another memoir. But I’ve stalled on it, as it also circles around very hard, very personal subject matter, and I admit to not having the stomach for it right now. I hope that will change, as I think it’s also an untold story that could be helpful to others.

Bonus question: Have you ever taken a picture of a weird bird?

Do fancy chickens count? If so, yes! I found an alarming quantity of these images on my phone when you asked this question.

Anne Pinkerton can be found on the web at AnnePinkertonWriter.com where you can also purchase her book and read her blog.

One thought on “5 Questions With Anne Pinkerton”