Welcome to Five Questions With—An interview series where I talk with some of my favourite writers, publishers, agents, and other industry folks. This week I’m talking with Murgatroyd Monaghan about the politics of erasure, what it means to write Autistically, and why poetry should sometimes hurt.

Your book, white spaces where we learn to breathe is already creating a huge buzz of excitement in pre-release. What is the heart of this project and what can readers expect from it?

This question makes me so happy! The heart of this project is the question of white spaces: what spaces are white spaces, how did they become that way, how do we all navigate them and exist within them, and how conscious are we of allowing vs challenging white space? Also, what have the consequences erasing BIPOC spaces been? Our land is Indigenous land that has been annexed and coopted by white people, who inserted white spaces here, and who now largely make the rules that govern the spaces we live within. But what if we refused to follow those rules? What if we rewrote – or unwrote – those rules to change the spaces we exist in? What about in the literary world? As an artist, my preferred medium is language, and I wanted to explore this concept of white space visually, inserting text onto the page in uncomfortable ways that challenge what those of us who are used to existing in white spaces might be familiar with. It’s the experiment that never ends, because even now, as I plan my book tour for this summer/fall, I find myself asking: where should I book this reading? In a BIPOC owned/led space? Or should I insert this book and its poems into traditionally white space? As to what folks can expect, please expect a meditative collection of poems that honour the lives of BIPOC who lived and died in white spaces as well as poems that reckon with the experiences of myself, my family members, my community members, or others, as we navigate the ways whiteness takes up space in our lives, minds, and bodies.

You are so honest and real in your conversations about neurodivergence and creativity. What is something you wish the publishing world understood about making more inclusive spaces and processes for neurodivergent writers?

Neurodivergent people are some of the most creative people I know. I’m going to maybe upset some people here, but I think embraced neurodivergence is a marker of an excellent artist/writer. To be an artist, a poet, a writer, is to challenge the norm. It is to live in the margins of society and experience humanity in a different way. Neurotypicality, by definition, is comfortable. It’s what we’re most comfortable with. Society consumes neurodivergence for entertainment, we have these quirky characters who miss social cues and make us laugh at them, and that’s a comfortable position for neurotypicals to keep Autistics in, in general, but the same society is not comfortable with us as creators because we challenge their world view. There’s an appropriation of neurodivergent culture in popular culture, but we are constantly squeezed out of the publishing/literary world.

I’ll tell you a couple of stories. Firstly, when I started breaking into the world of spoken word, I remember I won a slam in Northern Ontario called Wordstock, and the festival organizer publicly contested my win because she said I “looked awkward”. So here we have this idea of how a spoken word poet should look, and anything that doesn’t conform is awkward, it’s uncomfortable. Another example is that recently, I received a mentorship that I couldn’t benefit from because I didn’t understand the concept of how communication should work when there’s no exact schedule for connecting (it was “connect when you’re ready” and “reach out when you feel you need it”), and then the notes on my work were written in a roundabout way that I assume was to preserve my feelings, making them unusable to me. The worst example is that often we get farmed for our creativity but then wiped out of the credit for our ideas or fired when we don’t operate neurotypically. The owner of a press reached out to me about editing a memoir for a rather prominent figure, but after I had put in hours of work into rewriting it, my work was stolen and I was removed from the project. The ghostwriter hired by the press had intentionally written something that was essentially point form and got me to ghostwrite, while only paying me very minimally for barely a copy editing fee and then removing my name. They sought me out because I was Autistic and they felt I would be easier to take advantage of and would do far more labour for nothing because I am neurologically unable to do things half-assed. Unfortunately, they were right. These are experiences I am still learning from.

Most simply though, the whole pathway of getting into writing as a career is not mapped out in an Autistically-friendly way. Like, okay, one could sign up to get a creative writing degree, if that was within one’s scope and ability and circumstance (although I would argue that’s not necessarily an ND-friendly path), but that still doesn’t show you how to get published. The whole literary world is close knit, it’s a lot of who you know, and meeting those people revolves around a lot of social events like literary festivals and book/magazine launches. That is inaccessible to a lot of us. The only reason I self-published my first book with a vanity press is because I had literally googled “how to publish a book” and when a bunch of links showed up for (what I now know are) vanity presses, I just figured that was how everyone did it. I paid all my savings to publish that book, despite a payment plan, and I didn’t have a good experience. With white spaces, I had a great experience obtaining a publishing contract, because I had used online spaces widely to be able to build community, unmask myself, and understand a lot more about the writing and publishing world.

Despite this, the publishing world needs us. There is no creativity without neurodivergence. I am planning a blog-post series for lit folks on how to make contests/lit mags/presses more neurodivergent-friendly, so keep your eyes out if that’s something you’re interested in! Adjacently, I am teaching a workshop this fall on Writing Autistically, and I’m pitching a four-week class on unmasking in writing for self-identifying neurodivergents, so watch for those too.

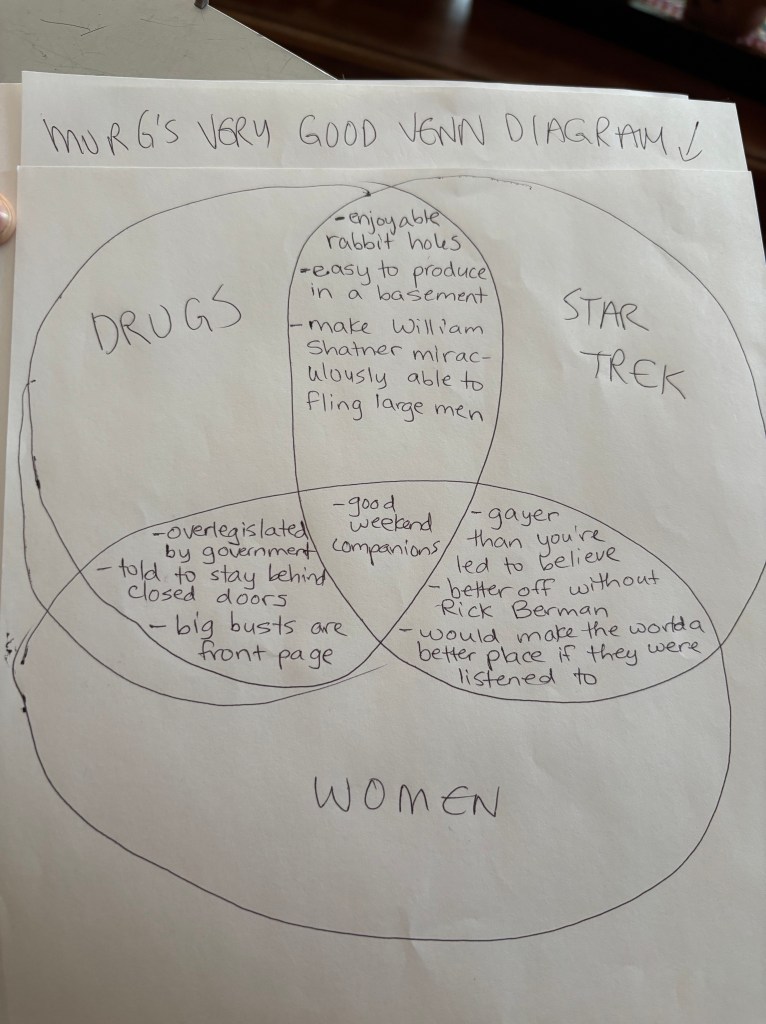

You write a lot about Star Trek, drugs, and women! Give me a Venn diagram of all three.

Star trek and drugs: enjoyable rabbit holes, easy to produce in a basement, make William shatner miraculously able to fling giant men

Star trek and women: Gayer than they let on, better off without rick berman, would make the world better if they were actually listened to,

Women and drugs: over-legislated by the government, told to stay behind closed doors, big busts are front page

All three: good weekend companions (Ed: Note: This whole answer is my favourite answer to anything, ever.)

What advice would you give other creatives as they navigate the sometimes overwhelming world of writing poetry?

I mean, I think that being a poet is a lifestyle choice. I have yet to see a wealthy poet or a poet of prestige who evokes the right kinds of feelings with their words. It’s hard to write good poetry from a position of privilege. It’s the art form. Poetry is a conduit for rage and grief that stem from injustices. So I think, embrace your vulnerabilities, embrace your ghosts, embrace the things that cause you mild inconvenience and deep, agonizing pain. And then challenge the systems and the people who made things that way for you. Tell the truth, and tell it with tears in your eyes and a knife between your teeth. Say it aloud, not just to yourself. You are now the intermediary; the poem lives on its own. Make it take up space. Maybe you haven’t found a publisher but every poet can find a stage. Find an open mic or a slam or a street corner and empower yourself to speak, because the world won’t make that space for you. Decolonize yourself. Forget about arbitrary and limiting colonial rules of spelling or grammar or storytelling and just say things how your soul sees them. Poetry is the jazz music of the phrase. It can take its time, it can push, it can follow no rules but the rules of the instrument and the heart, and a poet’s instrument is language. It should hurt. You, the artist, and your audience. It should cause discomfort. So if you’re already uncomfortable, you’re already a poet. You just haven’t told your story yet.

What is your favourite book and why?

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams

Reproduction by Ian Williams

When We Lost Our Heads by Heather O’Neill

Little Bee by Chris Cleave

I just really think everyone should read these books. They’re everything writing should be: brilliant, experimental, brave, true, strong, neurodivergent af. They follow no formula but the story, and stories happen in the mind and the body before they happen on the page.

Bonus question: Have you ever taken a picture of a weird bird?

Only a bird-of-prey. But I submit here this photo of my weirdo 30-lb cat, Thomas (Smoke Signals, in case you want the reference; also one of the greatest ND characters of all time) who gives me this look when I’m planning on writing on my laptop instead of feeding him.

Murgatroyd can be found on the web here and white spaces where we learn to breathe can be preordered here.

Leave a comment